Previously: An AI-Generated Script?

We never went through a canon [sic], or worked our way over dividing ridges without asking where the rails could be laid: and I really did think that the railway would have been here long before this... (Roberts, Documentary History of the Church, p. 248, emphasis added)

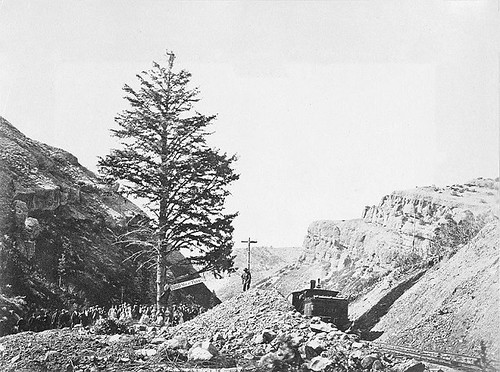

Is that another clue in our AI-scripted history telling us that the railroads were already here? Notice the photo above. Are they laying tracks, or just digging them out of the mud?

Think about it. The building of the transcontinental railroad would have been a massive undertaking, even today with the technology we have. They had only hand tools, horses and wagons, oxen and ox carts. But there are no photos of oxen in the historical railroad construction photos. Just men standing around and not actually doing any work. Why is that?

Of the six-year timeline during which the railroad was constructed, the majority of it was finished in only four. A total of 1,776 (is that number a coincidence?) miles of track were laid between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific companies, stretching from Sacramento, California to Council Bluffs, Iowa. That would need to include surveying, digging and perfectly leveling hard rocky desert and mountain soil by hand with shovels and picks; hauling thousands of tons of excavated dirt and rocks to "somewhere" (never mentioned), all with horses and wagons.

It meant somehow hauling in tons of gravel (ballast) to the site each day and laying (by horses and carts again) a leveled gravel base to support the hundreds of thousands of logged and cut wooden railroad ties, chopped by hand with axes and milled in unknown sawmills from some unknown forest.

Wooden ties laid directly on dirt without a preparatory gravel base would sink into the mud in harsh winters and wet spring snow melts, and the wood would quickly decompose. Without a gravel bed the iron rails would bend and buckle under the weight of trains if the logs were just laid directly on dirt. But a gravel support base is never mentioned in any of the stories we are supposed to believe.

Logistically, this is impossible stuff: hundreds of thousands of tons of base layer gravel in horse drawn wagons spread with hand shovels; entire forests logged (somewhere); big trees chopped by hand axe then milled and cut uniformly and hauled down the mountains on muddy dirt roads with horses and wagons. And then hundreds of thousands of uniformly cast iron rails brought in with horses and carts. Try to even picture this.

Yet we're told that the Central Pacific, beginning in 1863, built East from Sacramento, and the Union Pacific, starting at Council Bluffs in 1865, built West, until finally in 1868, the last few hundred miles of track was laid between Humboldt, Nevada, and the eastern mouth of Echo Canyon, Utah.

The tracks eventually met at Promontory Point, an isolated location some 30 miles west of Ogden, nestled awkwardly on a peninsula surrounded by the waters of the Great Salt Lake.

We hear that Brigham Young called some 4,000 LDS men and boys to go to work as graders for the railroad.

These laborers, unnamed and undocumented, wielding their shovels, picks, scrapers, sledges, wheelbarrows, and crow bars, literally carved a perfectly graded road through Echo and Weber canyons, filling in swales with untold tons of compacted earth, leveling ridges, cutting through the sides of granite mountains, constructing bridges and viaducts, and blasting out tunnels with black powder.

Again, notice the photo above in Weber Canyon (these are supposedly LDS workers), What does that look like to you? Are they laying tracks, or just digging them out of the mud? Are those brand new wooden ties, or do they appear old, with bent rails on the top?

The LDS part of the railroad was finished within a year, from May 1868 to May 1869. Nearly all the history books I've been able to find on the transcontinental railroads focus mostly on the financial aspect of the CP and UP, and Brigham's contract with them, leaving a lot of missing information about the actual construction process.

All the labor used by the railroad companies--the LDS Church's 4,000, the 10,000 Chinese supposedly brought in from China by the CP, plus the 10,000 Irish immigrants employed by the UP, as well as scores of starving Civil War veterans and American frontiersmen that supposedly flocked to the high wages offered by the railroads--are all undocumented.

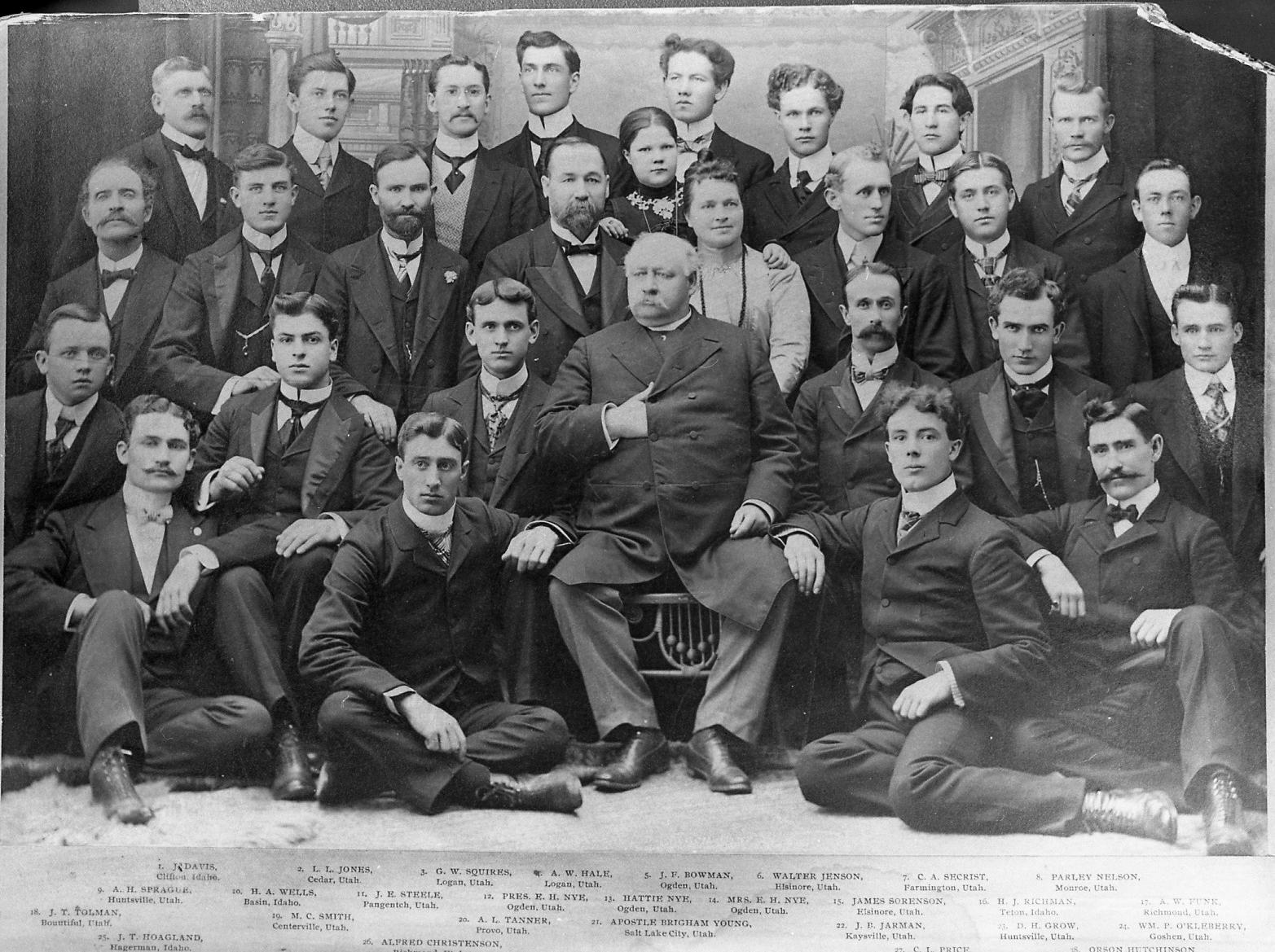

No matter what records you search in, whether the financial records of the UP and CP, or of the LDS Church, all you'll find is just a few names of men who were involved in the construction; names of men who are always written into the official history.

For instance, in the LDS Church, we have Brigham Young, his son Joseph D. Young and John Sharp (a quarryman), and a handful of others named in documents. But as to the 4,000 common laborers, we have nothing showing that they actually existed or assisted on the railroad in any way.

We are expected to believe that 4,000 LDS men and boys graded over 100 miles of road through mountainous terrain in only one year.

The entire story of the building of the transcontinental railroads reads more like Greek mythology than actual fact, replete with tales of heroic railroad workers created through anecdotal accounts, told decades after the events. Documentation of any kind: purchase documents for material, labor rosters, and personal diaries from workers are not just scarce, they are nonexistent.

Much of the "evidence" for the construction of the railroad comes from letters of correspondence between important financial figures like Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Grenville Dodge, Thomas Durant, Brigham Young, Joseph D. Young, and John Sharp. But just like we see with accounts of temple construction in early Utah, the great masses of common laborers remain silent about their part in the construction. No journals, and no photographs with named pioneers.

Because a match up of the railroad story is imperative to establish any kind of credibility for the temple construction narrative, the story of the transcontinental railroad must be carefully examined. This is a key piece to the puzzle in getting a clear picture of what was actually happening in the writing of the revisionist history in Utah, and why.

The railroad, we're told, was pioneer Utah's means of connecting economically and industrially to the outside world and bringing immigrants into the territory at a record pace (a week from New York or Boston instead of 3-4 months by wagons and handcarts).

From 1870 onward, hordes of converts flocked into Utah, as well as massive amounts of outside goods, helping Salt Lake and other Utah cities to grow at exponential rates--at least that's what we're told.

Let's dive in.

A Familiar Pattern

Central Pacific Myths and Legends

The snows gained upon the shovellers [sic] and the scrapers. Cuts were filling--the tunnel men had to excavate through twenty to 100 feet of drift before they reached the face of the cliff; and shut off from the world they burrowed like gophers... (Edwin L. Sabin, Building the Pacific Railway, p. 120, emphasis added)

Superintendent Crocker focused on boring tunnels in winter, as the men were sheltered inside. But black powder still had to be delivered to the job site, upwards of 500 kegs a day, at a cost of $54,000 a month. The powder was manufactured in Santa Cruz, then loaded onto wagons and hauled to the wharf, then loaded onto steamers, shipped upriver to Sacramento, and then hauled by teams of oxen through the mountains and to the tunnel sites.

Most other materials (including iron rails) were manufactured in the Eastern United States, loaded onto cargo ships and transported around Cape Horn to San Francisco (a six month journey). Once materials were taken upriver to Sacramento, they were loaded onto train cars and shipped to the end of track, and then loaded onto wagons and hauled to the construction sites.

According to Sabin (writing in 1919), some of these wagon trips were 24 miles long through unimaginable depths of snow:

As the snow gained and the working space became more crowded... Crocker loaded his extra laborers, their tools and supplies, upon ox-sleds; sent them across and down, to prepare the way through the Truckee River canyons near the Nevada line, or twenty eight miles.

He followed this thrust with a reinforcement of forty miles of track--rails, ties, fastenings, forty freight cars and three locomotives. For the twenty-four miles from Cisco to Donner Lake ox-teams and sleds hauled these tons of freight up to the summit through snow eighteen feet deep on the level, forty and sixty feet deep in the drifts... Here the loads were transferred to wagons and mud-skids and log-rollers for the four miles to Truckee. (Ibid, p. 122, emphasis added)

Not only did Crocker have "extra laborers" to send ahead to the Nevada border, but they somehow hauled multiple tons of iron rails on ox-drawn sleds and wagons over 24 miles of snow anywhere from 18 to 60 feet deep.

How was it physically possible for oxen to haul steel through 18 feet of snow? It's not like they had a snow cat to pack down the wagon path.

Remember, this is just a story, there is no documentation for this account from any of the 10,000 laborers. No journals. No photos.

Edwin L. Sabin's book, Building the Pacific Railway, published in 1919, is one of the major works on the transcontinental railroad. The main sources Sabin cites for his book are oral memories (produced 50 years after the fact), financial records of the Union Pacific, newspapers, and family records.

The book is poorly documented, and Sabin is vague about which sources are cited for specific claims (like hauling iron rails through sixty feet of snow). He is a great writer, very descriptive, and the book reads more like a novel than a work of historical nonfiction. And unfortunately, there is no way to know if anything he is claiming is true.

Sabin once worked in the Bancroft Library, and as I mentioned in my last post, Hubert Howe Bancroft, one man, is given credit for massive amounts of foundational American history, which should merit our criticism and suspicion.

Of the 15 tunnels carved out of the Sierra Nevada mountains, Summit Tunnel was the longest, spanning 1,659 feet. It took Chinese laborers nearly two years to build.

As the story goes, a shaft with a diameter of 6-12 feet was drilled from the top of the middle of the tunnel at a depth of 75 feet, which took two months. This allowed crews to bore out the tunnel from four positions: the two far ends and from both directions in the middle. Somehow crews working from both directions met each other in the middle.

Progress was slow and laborious. Hand drills were used to bore holes 2-3 feet deep. When about 20 holes were drilled, black powder charges were set off to blast out the remaining granite. Men would duck for cover and then clean-up crews would use wheelbarrows to haul off the loose rock and other muck created from the blast. Only 1-2 feet of rock face was removed from the tunnel each day.

The tunnel was built between 1865 to 1867, while thousands of other men were grading, laying track, harvesting lumber for bridges, and boring out other tunnels. Here is a photo of the abandoned Summit Tunnel today:

Remember, this is just one of the 15 tunnels and 37 bridges built through the mountains. To put this all in perspective, here is the timeline of the Central Pacific's progress:

- 1863: groundbreaking and 0 miles of track laid.

- 1864: 18 miles of track laid from Sacramento to Newcastle.

- 1865: 30 miles of track laid from Newcastle to Sierra foothills.

- 1866: 48 miles of track laid through the mountains to Cisco.

- 1867:40 miles of track laid from Cisco through Summit Tunnel and Donner Lake.

- 1868: 230 miles of track laid across Nevada.

- 1869: 200 miles of track laid from the middle of Nevada to Promontory Point, Utah.

- After rails were produced in iron mills they were loaded onto wagons and hauled to the nearest train station.

- Rails were loaded onto train cars and shipped to port cities like New York.

- Rails were unloaded and re-loaded onto cargo ships.

- Ships would sail from the Eastern seaboard, south down to Cape Horn, around South America, and back up to San Francisco, a voyage taking up to six months (some of the iron would arrive in California already rusted out).

- In San Francisco rails were unloaded at shipping docks and then reloaded onto barge or steam ships that would travel upriver to Sacramento.

- Rails were off-loaded at Sacramento and reloaded onto train cars, bringing the rails as far down the newly laid track as possible.

- At the end of track, rails were off-loaded and then reloaded unto ox-drawn wagons or sleds, dragging the rails through mud, snow, and rough terrain sometimes over 20 miles to the construction site.

Just imagine how long it would take to cut and shape just one tree into a square board with hand saws. Look at the precision of this bridge. How did they curve it so accurately? How was it leveled? How was it supported at the foundation? And notice of course that the bridge is already built. Where are the photos that show it under construction?

Union Pacific Impossible Logistics

- 1864: the UP spent this year planning and laying no track down.

- 1865: 40 miles of track laid from Council Bluffs and to North Platte.

- 1866: 260 miles of track laid through Nebraska and into Wyoming.

- 1867: 270 miles of track laid through Wyoming and reaching Cheyenne.

- 1868: 254 miles of track laid Green River to Evanston.

- 1869:262 miles laid from Evanston to Promontory Point

- The Big Sioux River Bridge

- The Platte River Bridge

- The Loup River Bridge

- The Medicine Bow River Bridge

- The Green River Bridge

- The Weber River Bridge

The Union Pacific's base was at the west or frontier side of the unbridged Missouri, upon which navigation was practicable scarcely more than three months in the year, between freshet and low water. The nearest delivery of supplies was at St. Louis; thence they must be transported by steamboat up-river 300 miles; or at the end of the railroad then building across Iowa--the Chicago and Northwestern being distant over 100 miles. From end of railroad transportation was by wagon to the Missouri, and by ferry to the Omaha side. (Building the Pacific Railway, p. 142)

Sabin claims that the UP became proficient at laying over 1 mile of track per day, which means that shipping companies would have to ship 40 train carloads of iron every day to the end of track. Judging by the paragraph above, this would have been a logistical nightmare, especially on a river that was only navigable three months out of the year. This means that for the UP to continue apace in laying 1 mile of track per day, all the materials for an entire year would have to be shipped in a three month period. The math adds up to over 14,000 carloads of iron in just three months.

And remember, construction crews would've been ahead of the end of track by at least a few miles at a time, which means that these 14,000 carloads of iron had to be offloaded onto wagons and hauled to the jobsite with horses or oxen.

Keep in mind that this was just for the track, and excludes the material for the iron and wood bridges that were constructed along the way.

Do you really think this was possible? Unfortunately, there is no way to know because there are no records or documents verifying the delivery of this material.

Despite the alarming lack of official records and documents, Sabin paints the following picture of merry workers laying track in perfect rhythm to the robotic commands of their UP masters, as if thousands of men were functioning as a single organism:

The first construction train pulled in, halted noisily, and dumped its thunderous load. The construction train backed out; the boarding-train [carrying workers] pulled out to clear the way for the charge of the iron-truck hauled by rope and galloping horse with a shrieking urchin astride. Forty rails were tossed aboard; the iron-truck rumbled full speed to end o' track, passing another truck, tipped aside to give it right of way.

The rail squads, five men to a squad, were waiting on right and left; two rails were simultaneously plucked free, to the truck's rollers, and hand after hand were run out to the ties. "Down!" signalled [sic] the squad bosses, almost in one voice. The end of each rail was forced into its chair. The chief spiker was ready; the gauger stooped; the sledges changed--another pair of rails had been set and truck rolled forward over the preceding pair, interrupting the busy hands of the bolters.

Thirty seconds to each pair of rails; two rail lengths to the minute, three blows to each spike, ten spikes to a rail, 400 rails and 4000 spikes and 12,000 blows to a mile. To every mile some 2500 ties--say 2400 at the outset, 2650 on the grades--at $2.50 each, delivered. The roadbed is ever calling for more and more; six and eight-horse or mule teams toil on from end o' track with spoils from the immense tie-piles; in the mountains, the tie camps are heaping others by the thousands.

The magnitude and precision of the undertaking awed beholders. The system reminded of the resistless march of the military ants of South America, or of a column of troops occupying a territory. (Ibid, p. 157-58)

So typical of Sabin, he's describing the event in such rich detail as if he was there himself, but he wasn't. He offers no documentation for this passage, names no person recounting a memory, and cites no journal. Yet his descriptive vignette paints a detailed picture in the mind, told with such boyish excitement as to invoke a feeling of appreciation for these unknown, unnamed, and undocumented railroad pioneers.

Are you still believing any of this?

The Mormons and the Race to the Finish

- Heber Robert McBride

- John Gerber

- Brigham Young: sources include letter of correspondence to UP officials and other LDS leaders.

- Brigham Young, Jr.: cited as an early negotiator with the UP in Chicago.

- Joseph A. Young: cited as a contractor for the UP in charge of LDS crews.

- John Sharp: cited as a partner with Joseph A. Young.

- Ezra T. Benson: cited as a contractor for the grading of the Central Pacific from Ogden to Monument Point.

- Lorin Farr: mayor of Ogden who partnered with Benson.

- Chauncey W. West: a Weber Stake President and contractor for the CP.

- Lorenzo Snow: contractor for the CP.

- John W. Young: another son of Brigham Young who coordinated with UP officials and oversaw work crews in Echo Canyon.

The work continued. Those were the orders: work all winter, as all summer and fall. Thaws succeeded freezes, but the snow had gathered twenty feet, and the grade, shovelled [sic] partially bare, was a white-walled galley. To descend from the divide into Echo Canyon a tunnel of 770 feet, approached by two lofty trestles [bridges] of 230 feet and 450 feet, was necessary, or the grade would touch the 116-foot limit. The hard-frozen red clay and sandstone required nitroglycerin, and called for an expense of $3.50 a yard. But [Grenville] Dodge... could not wait upon the tunnel.

By a zigzag temporary route named the "Z," of ten miles, the track circumvented the tunnel, and thus material was shunted down. The rails could not wait for the clearing of the grade either; they were laid upon the ice and glaring snow--a whole train, from engine to caboose, slid sidewise into the canyon's bottom, carrying with it iron and ties.

The tracks south the canyon bottom; and here the mushy ground yielded until crowbars were used to steady the superstructure while the construction train crept over. (Building the Pacific Railway, p. 190-91, emphasis added)

What on earth did we just read? Does this sound believable at all? Can you imagine a scene of scores of men using crowbars to steady a massive train, carrying thousands of tons of iron, on a track built over ice and snow in the bottom of a canyon?

As it turns out, this 770 foot tunnel described by Sabin is also Tunnel #2 built by the Mormons, which Stevens claims was only 150 feet long. Here is a photo of the mouth of it:

Does that tunnel look tall enough for a train to fit inside? And let's take a look at these "workers". The well-dressed man on the left has some high ambitions with that hand saw. The man straddling the railroad tie in the middle seems to be contemplating carving something into the tie with a wooden peg and a ladle-shaped hammer. It doesn't look like he'll be very productive. The man on the right holding the square, well, he just looks confused, even dumbfounded.

I don't know about you but I don't see any actual work going on this photo...or any photo we've seen for that matter.

These photos of the railroad can be found in the book Westward To Promontory, a compilation of photographs taken by A.J. Russel. It was not published until 1969, long after the photographer's death.

Another interesting photo in the book is of the 1,000 mile tree. A pine tree in Echo Canyon that marked 1,000 miles from where the UP began laying track in Nebraska. Tell me, what is a telephone pole doing in this photo, a thousand miles from nowhere?:

And if you zoom in a little you can see a man who climbed to the top of the tree for the shot...except he appears to be sitting on nothing. A definite anomaly showing how these old photos have been tampered with. I recommend clicking on the link above to the book and looking at all the photos. None of them show any actual construction being performed.

The Mormon contract with the UP stipulated that the work be completed by November of 1868, originally only six months. But we're told that crews worked all winter long, through ice and snow, to reach Promontory Point by May of 1869. Yet, in less than a year, Mormon crews had graded and helped lay track over 100 miles of rough terrain, over half of that through rugged canyons. Quite an accomplishment for a horse-n-buggy society.

The Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory was held on May 10 of 1869. This was supposedly when the "last spike" was driven into the iron rails connecting the last length of track between the CP and UP. Brigham Young did not attend, we're told, because he was on a trip to southern Utah, but was represented by John Sharp. However, Sharp is missing from any photos.

There are anomalies surrounding the ceremony, which transpired at high noon (is this another clue?).

There are no official records or documentation proving the meeting actually took place. Details of the day's events come from interviews from attendees (like Grenville Dodge and Sydney Dillon of the UP) conducted decades after the fact. It is claimed that over 20 newspaper reporters were in attendance that day, but because of "noise and confusion," none of them were able to fully report the story, so accounts are contradictory.

No one knows how many people were actually there, and estimates range from 500 to 3,000. These numbers are based on the photographs below:

The Hidden Hand...of History Writers

Heber was also a Freemason. In 1823 he received the first three degrees of masonry in the lodge at Victor. The year following, himself and five others petitioned the chapter at Canandaigua, the county seat of Ontario County, for the degrees up to the Royal Arch. The petition was favorably considered, but before it could be acted upon the Morgan anti-mason riot broke out, and the Masonic Hall, where the chapter met, was burned by the mobs and all the records consumed. (Life of Heber C. Kimball, p. 26)

There are two problems with this claim. First, there is no contemporary evidence that the Masonic Hall burned down in 1824. There are no records or newspaper articles in Canandaigua indicating that a fire took place in a masonic building. Here is what the structure may have looked like in the 1820s:

Don Carlos Young, as you may recall, was an architect in Utah who finished the Salt Lake Temple after Truman Angell died in 1887. He is also given credit as the designer of the Church Administration Building in 1917, another Old World beauty.

In my opinion, some elements of Royal Arch freemasonry have survived and were passed down in the LDS Church. The question is did this tradition originate with Heber C. Kimball?

They used their secret signs and words to identify any fellow gang member who had made the covenant. It didn't matter what crime his fellow gang member committed, he would be protected by the other gang members. They were able to murder, rob, steal, and commit whoredoms and all kinds of evil, violating the laws of the land and the laws of God also. Anyone who belonged to their gang and revealed their wickedness and corruption to the world was to be tried, not according to their country's laws, but according to the rules of their gang society, which had been established by Gaddianton and Kishcumen. Now these were the secret oaths and covenants Alma commanded his son not to make public, to prevent the resulting destruction. (CoC, Helaman 2:32)

Had Kimball violated some oath, or was it just an accident?

Join me next time as we dive into rock quarries and stone walls...

If you're interested in further research that questions the railroad narrative, see chapter 15 of James W. Lee's book, The One World Tartarians, click here to read that chapter.

Also, for comparison, here is a video about the transcontinental railroad constructed in Australia, another story with missing logistics and record-breaking construction speed:

There were transcontinental railroads built all over the world, all echoing the same construction story: super-fast speed with missing logistics. One of the most unbelievable was the Trans-Siberian railway built in Russia, spanning nearly 6,000 miles, built by 62,000 workers, and taking only 13 years.

And here is a video speculating that train technology may have been inherited:

Postscript: A Look at Union Station in Ogden

This thing had 33 (masonic number) hotel rooms, a restaurant, a barber shop, and office space. But the best part about this building is it only took two years to build.

Construction on the new Union Station was completely halted throughout 1887, as the UP had some financial business to attend to that year. But never fear, work resumed in 1888, and by July 31 of 1889 the building was completed and open for business.

.jpg)

.jpg?mode=max)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

_p836_OGDEN%2C_UNION_RAILWAY_STATION.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment