From 1888 to the Capstone Ceremony

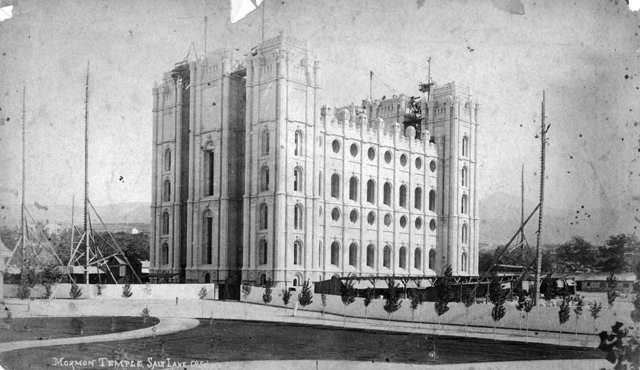

We can clearly see four derricks placed around the temple, but in awkward positions. They appear as fragile stick figures drawn in to the photograph. The derricks don't rise above the total height of the temple which makes me wonder how they were used to hoist granite blocks up to the spires. Also note the lack of ropes or pulleys on the derricks and the complete absence of the alleged steam engine.

Now take a look a the photo below, showing the spires completely finished and surrounded by scaffolding. Is this a "construction" photo, or is this an image of an already-completed building with a little scaffolding on it?

Zoom in on the towers. You'll notice that the scaffolding isn't supported by anything. You'll also notice anomalies in the skies. I wonder how workers were able to climb up to the scaffolding from the roof? Do you see the lone man standing on the right side of the roof just above the parapets? He's a long way down from the scaffolding. Also notice the mountains on the right side of the temple, they appear to have been erased and drawn back in. The photo seems very off to me.

There are virtually no other details given to us on the construction of the spires, we are just expected to believe that they were finished sometime in the early 1890s.

They were made of sixteen gauge hammered copper by Samuel Backman of Salt Lake City. These ornaments are fastened into the capstones of the spires by means of iron rods, which reach to an insulating joint, about halfway up the interior of the finials, and are counterbalanced by iron weights. The inside of these towers is inaccessible at the present time [1960] and thus it is impossible to describe the exact suspension system utilized. These ornaments were initially gilded in gold leaf and each was illuminated with eight one hundred candlepower incandescent lamps. (Everlasting Spires, Loc 2503-2517)

Copper, granite, and gold are electrical conductors. Were these finials some type of old technology used to send or receive power? The dome of the capitol building in Salt Lake City was also constructed of granite and copper, and according to some theories, may have used magnetricity to harvest energy from the ether. Tesla had a patent on a technology that could send electricity through the air without wires, but we're told that it was not developed because it was deemed "unsafe."

Did Tesla just rediscover something that had already been used centuries earlier?

There is another scientific phenomenon known as Scalar Waves. They are longitudinal waves that are little understood by scientists. They have magnitude but not direction, travel faster than the speed of light, and seem to transcend space and time. Old World building spires may have actually been antennas for these waves, and used for global communication centuries ago. Watch this short video to learn more:

According to LDS historians, the spring of 1893 saw both the Salt Lake Temple and Saltair Pavilion finished. We're told that construction of the Saltair only took three months during the winter of 1893. How in the world did the Mormons finish the interior of the temple and the Saltair at the same time?

A Moorish Wonder Built in a Year

According to an 1893 article in the Contributor, the annex building was constructed between May 1, 1892 and April 5, 1893, and finished just in time for the temple dedication on April 6. It was said to have been designed by Joseph Don Carlos Young, the son of Brigham Young who took over as Church architect after Truman Angell died.

...the Annex is a capacious building. It is beautifully finished in white, the windows being stained glass. The basement of red sandstone, with pilasters and buttresses of granite, and the upper part of oolite from Sanpete, the same material as that of which the Manti Temple is built. The columns on either side of the main entrance are Utah mosaic marble. When the temple is in use the annex will serve as the principal entrance, the connection with the Temple being made by a well-finished corridor twelve feet broad, which is brilliantly illuminated by two hundred incandescent lights... ("The Salt Lake Temple," p. 283)

The corridor was actually a 100-foot-long tunnel. James Talmage offers a little more detail:

The foot of the stairway [leading to the basement] marks the beginning of a semi-subterranean passage, which runs south ninety feet to the Temple wall. This passage receives air and and natural light through side windows in three large ventilator cupolas which rise six feet above the ground. Artificial illumination is supplied by three electroliers, each holding twelve globes...Heavy doors divide the Annex from the Temple. (Talmage, The House of the Lord, p.68)

There are no logistics available on the construction of the temple annex. We are just told that it was built. There is nothing on how the marble columns were shaped, or how the tunnel was excavated, built, and illuminated in only one year. (Keep in mind that the new annex built during the 1960s took four years to construct.)

Another strange building was the old boiler house, also having a Moorish look. The only photo I can find of this building comes from the Contributor article quoted earlier. It's a physical book so I had to take this picture with my phone:

Why would you need such a building for a boiler house? What was the point of the Moorish cupola with the finial and spire on top? What is this Russian-looking architecture doing in the American West? And notice the pile of rubble in front of the archway. Was this "new" building already in ruins?

The article claims that this building was located three hundred feet away from the temple and housed four large boilers in its basement. Water was heated to 170 degrees and either pumped or gravity-fed to the temple in a 12" pipe and then distributed into smaller pipes and directed to heating radiators spread throughout the building. The water recirculated back to the boilers and was re-heated in some kind of closed loop (See, the 1893 Contributor, "The Salt Lake Temple," p. 282).

Now think about this logically for a moment. Remember, it is claimed that all of this work (the annex, the plumbing and electrical, the boiler house, the interior of the temple) was completed in only one year. The plumbing job alone would've been a massive industrial project, even with the technology we have today. All of the piping would have to be installed on the inside of the wood framing of the interior rooms so it could be hidden from sight. The pipes would have been installed on the interior granite walls of the temple and secured with metal strapping.

This had to be done before any interior framing or finish work could begin. This plumbing job alone, even if contracted to experienced industrial plumbers with large crews of men, could have taken well over a year. We're not told what kind of piping was used and where it was sourced from. This was before PVC or other types of plastic piping was invented, so lead or cast iron was probably used. This is very heavy material and takes a lot of time to fuse fittings together.

I have a little experience with plumbing and used to sell plumbing and mechanical parts to contractors for commercial and industrial jobs. Even today some of these projects (including LDS temples) can take several months or even a year or two. And again, the plumbing and electrical has to be installed first before any finish work can even begin.

We are not told who installed the plumbing on the temple, or the electrical, or who hand-carved and installed the fine carpentry, nor given any details at all about any of the interior work. We are only given later descriptions after the work was completed.

A book of remembrance was published in 1993 commemorating the 100-year anniversary of the Salt Lake Temple. It states that the interior was "roughly-framed" by April of 1892, but cites no sources to verify the claim:

Once the capstone is laid, the enormous task of completing the roughly-framed interior begins. Now craftsman have to plaster and paint the walls, lay flooring, make ornate moldings and other woodwork, install electrical wiring, lighting, plumbing pipes and fixtures, and furnish and decorate the temple. They have only one year to finish. (The Salt Lake Temple: A Centennial Book of Remembrance, 1893-1993, p. 60)

We're told that John R. Winder, the second counselor in the Presiding Bishopric at the time, was given charge of the interior work of the temple on April 16 of 1892. Talmage only gives us one paragraph about who these workers were, and he basically says nothing about them:

Under his [Winder's] supervision, work on the interior of the Temple progressed at a rate that surprised even the workers. Laborers of all classes, mechanics, masons, plasterers, carpenters, glaziers, plumbers, painters, decorators, artisans and artificers of every kind, were put to work. The people verily believed that a power above that of man was operating to assist them in their great undertaking. Material, much of which was of special manufacture, came in from the east and the west, with few of the usual delays in transit. (The House of the Lord, p. 56)

Talmage is infusing this paragraph with a sense of the supernatural. This is a bait and switch. He offers no details about the workers except that they were skilled. He doesn’t name any laborers, nor give any details about their training or experience working on the interior of the temple.

This is another pattern: no details about the logistics but heavy focus on the supernatural, describing some "power above that of man" helping them to finish the edifice. Even the materials being shipped across the country were immune from the "usual delays." This story is simply too good to be true.

We need to stop here and ponder why God would assist the LDS people in building such an over-the-top edifice when Nephi says that God condemns "fine sanctuaries that rob the poor." Nephi did build a temple, but it was not built of the fine things used on Solomon's temple. The Kirtland temple was also very simple, and it is the only modern temple in which the Lord has ever appeared. It is clear from modern scripture that the Lord rejected the LDS Church with their dead, because they did not finish the Nauvoo temple in time. He also promised them that if they hearkened unto His voice and unto His servant Joseph's voice, that they would not be moved out of their place. But they were moved out of their place and forced to flee to a barren desert (which I believe was full of abandoned buildings).

So why would God reward a disobedient people with supernatural assistance in building unnecessarily extravagant buildings for temple work that He had already rejected? Why would God approve of a system where the poor would be asked to sacrifice their time and effort to construct massive buildings while struggling to feed their own families?

Furthermore, why would God condone Church leaders for feeding themselves off the labors of the flock so they could bask in opulence while the poor built mansions for them?

No. I do not believe there was any supernatural "help" given to the LDS people to construct buildings that were beyond their means to construct. James Talmage is telling you a feel-good story, nothing more.

And speaking of feel-good stories, let's move on to the temple interior.

Order out of Chaos

When the capstone of the Temple was laid, the scene inside the walls was that of chaos and confusion. To finish the interior within a year appeared a practical impossibility. (The House of the Lord, p. 56, emphasis added)

The words "chaos and confusion" should induce a familiar ringing in the ears of those who study conspiracy. Modern secret societies, at least those vying for global dominance, have used an axiom known as "ordo ab chao," or order out of chaos.

The phrase has a dual meaning. To the aspiring Freemasonic initiate, ordo ab chao is the motto of the 33rd degree, signifying the arduous journey through the successive degrees. But to the global elite, those who have advanced far beyond the lower degrees, the phrase means something much darker. It alludes to the philosophy of Frederick Hegel: using conflicting philosophies (chaos) to deceive the masses into submitting to some kind of arbitrary rule (order). This is known as the Hegelian Dialectic. In America the illusion of a choice between right and left has been used for this very purpose. It's the age-old divide and conquer strategy.

This begs the question: was Talmage a fellow initiate? And was he writing this Masonic philosophy directly into the temple narrative? It's important to note here that Talmage was one of the Church leaders on a 1921 committee which voted to take the Lectures on Faith out of the Doctrine and Covenants. This vote was conducted in secret and not presented to the ordinary Church members. In this sense, Talmage assisted in replacing faith in Jesus Christ with faith in the institution. This was six years after he published his famous treatise, Jesus the Christ (1915). It makes one wonder how Talmage could promote Christ on the one hand, yet destroy faith in Him on the other?

Regardless, the temple narrative is imbued with a sense of supernatural abstraction. Nameless laborers scurrying like ants and bees to bring order out of a jumbled interior mess. And in record time no less. We find the account completely void of logistics, yet replete with paragraphs like the following:

The rapidity with which the work progressed was nothing short of marvelous. Obstacles in the way of obtaining material and accomplishing tasks that it had appeared impossible to overcome only with great difficulty and delay, were swept away as if by magic. It was evident to all who took note of the proceedings that affairs were being shaped by more than human hand. (1893 Contributor, "The Salt Lake Temple," p. 282, emphasis added)

"As if by magic," now that's another interesting phrase. Yes, the entire year between April of 1892 to April of 1893 seemed magical indeed. To finish not only the interior of the temple, but to construct the Saltair from start to finish in only three months while simultaneously completing the finishing touches on the temple--now that's a mind bending conundrum. How was it accomplished? Yes, some kind of "magic" seems like the only plausible explanation. This level of detailed work could not be repeated today in the same timeframe, even with our modern training, technology, and tools.

Now, keep in mind that photographers never show us the interior of the temple. There is not one single photo of the temple interior before 1892 showcasing the steam engine that powered the derricks, the railway built 40-plus feet in the air, the interior stone work and scaffolding, the construction of the 80-foot granite stairways, or the vast emptiness of a 200-foot tall hollow stone structure, with circular stone columns at the corners.

In all the searching I've done on this temple, I was only able to find a single photo of work being done on the interior. It comes from the book, Set in Stone, Fixed in Glass: The Mormons, the West, and Their Photographers, published as photographic history of Utah in 1992.

The only description the book offers is the following:

Workmen on the interior of the temple have their picture taken in 1892 while working to complete the building for dedication the next year. (p. 167)

Again, no names of the workmen, no details about the room they are working on, and no exact photograph date. I had to take this photo of the physical book page with my phone. Here is a close up of what appears to be framework for the elevated seating in the Assembly Room:

Here's what this room looked like before the recent renovation:

What do you think? Is the construction photo real? It doesn't show us the true height of the room, or the large windows. Take another look at the elevated seating. It doesn't appear to be high enough compared to the height of the men standing on the floor. In addition, the rough-framed stage doesn't appear wide enough.

Notice the angle of the framing under the elevated seating. If you scroll back up to the construction photo this angle is hidden, and the wooden support studs (4x4s?) look too large (and too close together) to be framing for the columns.

The Main Assembly Room which with its vestries and the end corridors occupies the whole of the fourth floor, is one hundred and twenty by eighty feet in area, and thirty-six feet in height. A commodious gallery extends along both sides, and but for the space occupied by the stands, includes the ends. At either end of this great auditorium is a spacious stand,--a terraced platform,--a multiple series of pulpits...

This great room is finished in white and gold. From the paneled ceiling large electroliers depend, and these with the cornice lights present a total of three hundred and four electric globes. In the rear of each stand are commodious vestries with entrances on either side. In each corner of this imposing auditorium, is a spiral stairway leading to the gallery; the stairway is of graceful design with hand-carved embellishments. (House of the Lord, p. 72)

Think of the sheer amount of man hours that would've been required for just this one room. Take a look at all the hand-carved trim around every window, which also spans the ceiling and the walls. Just the carpentry alone could have taken years for this room. Remember, power tools were not invented until 1895, so all the exquisite detail you see would need to be carved with hand tools, and somehow carved with perfect symmetry.

Do you really think this was possible to complete in less than a year--while workers were simultaneously finishing the rest of the interior while constructing the annex, its 100-foot tunnel, and the Moorish boiler house, simultaneous with the construction of the Saltair?

Let's take a look at the Celestial Room:

According to Talmage:

This is a large and lofty apartment about sixty by forty-five feet in area and thirty-four feet in height...In finish and furnishings it is the grandest of all the large rooms within the walls...it may be appropriately called the Celestial Room...Along the walls are twenty-two columns in pairs, with Corinthian caps; these support entablatures from which spring ten arches, four on either side and one at each end...The ceiling is a combination of vault and panel construction elaborately finished. Massive cornices and beams separating the ceiling panels are richly embellished with clusters of fruit and flowers...Eight electroliers with shades of richly finished glass depend from the ceiling, and each of the twenty-two columns holds a bracket of lights in corresponding design...(House of the Lord, p. 70)

Again, there are no construction logistics available describing how this room was framed and finished, no journal entries from the workers detailing the work completed there, and no photographs of the room under construction. There are no details about where the lumber was milled and shaped, or where it was shipped from.

The veil in the Celestial Room is guarded by a graven image of a strange woman. Temple patrons know her as "the woman at the veil":

Why would the LDS people sculpt this woman and place her in such a critical area in the temple--especially when they had scripture that specifically prohibited the making of graven images?

The official story is that Don Carlos Young, while visiting New York City in 1877, purchased three statues (of a woman and two children) in the Italian district and brought them home to Utah. Sixteen years later Young employed a sculptor named Cyrus E. Dallin to make a replica of the statues out of plaster to be placed in the temple. He also carved the seashell engulfing the woman. Actually, historians speculate that it was "most likely" Dallin that carved the statue but there is no documentation proving this. There has also been a lot of speculation as to the symbolism intended by the statue.

LDS Historians assure us that the image was not intended to be "the Virgin Mary, Venus, Aphrodite, Heavenly Mother, or Jesus," yet offer no proof or documentation. The truth is that one really knows how this statue got there or what it really means.

According to the account, there were originally wings on the woman and Young had them removed because he thought it would offend Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and John Taylor from beyond the grave. Apparently, the holes that secured the wings can still be found on the back of the statue.

The story is very, very strange, and the details don't add up at all. But there may be some answers to be found if we look to Greek mythology. The story of the goddess Aphrodite begins in the sea. The name aphros is derived from sea foam. The origin story is quite disturbing. Apparently, Cronus had his father Uranus' genitals severed and thrown into the sea, and Aphrodite emerged from the ensuing foam. She had no mother.

Because she emerged from the sea she is often depicted with a seashell. She was venerated as the goddess of love, desire, and fertility. The legends that surround her are fraught with tales of seduction and unfaithfulness. She was also the patron goddess of prostitutes. She has often been depicted with her first two children on either side of her: Eros (Cupid) on the left and Harmonia on the right.

The same false gods have moved from one culture to the next since the dawn of man. The only thing that changes are the names of the gods. Aphrodite was not a new goddess to the Greeks, her character was based upon a much older goddess, Astarte.

Astarte was venerated by the Canaanites and the Phoenicians. She was often depicted with wings and was even known as the Queen of Heaven. Other goddess in other cultures fitting this description were Inanna, Isis, Anat, and Nut. Going back even further, all these goddess stem from Semiramis, Nimrod's wife and the mother of Tammuz. These three were the original pagan trinity.

So who really is the "woman at the veil" in the Salt Lake temple? I don't know, but I truly believe that whoever actually built the Salt lake temple were a people deeply immersed in occult and pagan worship.

Did Don Carlos Young have the wings removed from a found statue so that it would be more palatable to temple patrons? Who knows? But I'm not buying the official story that Young purchased the statues in New York, held onto them for 17 years, and then had a sculptor copy the models and place them in a seashell.

I don't have space to cover every room in the temple, but a few more are worth mentioning.

Talmage describes the Holy of Holies as "by far the most beautiful" of the smaller rooms. He describes the room as follows:

It is raised above the other two rooms and is reached by an additional flight of six steps inside the sliding doors. The short staircase is bordered by hand-carved balustrades, which terminate in a pair of newel-posts bearing bronze figures symbolic of innocent childhood; these support flower clusters, each jeweled blossom enclosing an electric bulb...

The floor is of native hard-wood blocks, each an inch in cross-section. The room is of circular outline, eighteen feet in diameter, with paneled walls, the panels separated by carved pillars supporting arches; it is decorated in blue and gold. The entrance doorway and the panels are framed in red velvet with an outer border finished in gold. Four wall niches, bordered in crimson and gold, have a deep blue background...The ceiling is dome in which are set circular and semicircular windows of jeweled glass, and on the outer side of these, therefore above the ceiling, are electric globes whose light penetrates into the room in countless hues of subdued intensity. (House of the Lord, p. 71)

Here's a photo of the room:

I don't see the bronze figures displaying the innocence of childhood, but this seems like very strange artwork to put in a temple, especially in the Holy of Holies. We do have examples of what the bronze figures may have looked like, which we find in the capital building. Here is a photo I took myself while visiting there:

Behold, the gold, the silver, and the silks, and scarlets, and fine twined linen, and all manner of precious clothing, and the harlots are the desires of this great and abominable church. (1 Nephi 3:13, RE, emphasis added)

I have to concur with Mormon on this. He saw our day, and called us out for our love of the vain things of the world:

For behold, ye do love money, and your substance, and your fine apparel, and the adorning of your churches, more than ye love the poor and needy, the sick and the afflicted. (Mormon 4:33, RE, emphasis added)

So did the LDS people really build this temple and adorn the interior with all these precious things? As always, I don't really know, but ironically, the entire story is a catch 22. On the one hand, if the temple was already here in 1847 then the LDS Church is lying about their history, but if it wasn't here and was actually built by them, then they are in violation of scriptural commandments to take care of the poor instead of building fine sanctuaries.

Either scenario doesn't bode well for an institution claiming to be God's one and only "true church."

Before I end this post, there is some confusion to clear up in the account. In Henshaw's book, he claims that work on the interior actually began as early as 1889 after the roof was installed on the temple. This would have given the workmen four years to finish the interior. However, Henshaw does not cite any sources for this claim. He subtly adds it as a nonchalant supposition:

The roof was on, and if the laborers could sustain the same rate of progress they had managed in recent years, they would finish the spires in the next season or two, perhaps by the end of 1891, or early 1892 at the latest. It was, therefore, time to start on the interior, and some of the rooms were going to take years to complete. (Forty Years, p. 478, emphasis added)

I was perplexed by this statement and reached out to the Church History Library to see if there are any documents verifying this claim. Personnel responded to my request and assured me that work on the interior did begin in 1889, and sent me links to some documents to study. But unfortunately, what I found doesn't prove a thing.

All Official Documents Point to the One-Year Miracle

Unless there is some thorough system adopted and energetically carried out, it is evident, from what we learn, that we shall be disappointed in the expectation of finishing the building in one year. There is an annex to be erected, and the interior will require a large amount of labor. (See full Journal entry here, emphasis added)

Cannon's words here seem to imply that work on the interior has just begun. Later in the this entry, Cannon moved to place John R. Winder in charge of the interior work. Winder was 72 years old at the time. On the next day, April 12, he writes about taking steps to decorate the temple. The next significant mention of the interior comes on Cannon's Sept. 8, 1892 entry, wherein he talks about steam heating, elevator shafts, and electric lighting.

Logically, the next place we should look for construction details about the interior work is in Winder's personal papers and documents. But the only journal available for Winder has entries made in the 1850s, there is nothing from 1892 to 1893. In 1903, Winder wrote an article that was published in the Young Women's Journal. Here is what he said about the interior work:

Those of us who were permitted to assist in the finishing of the interior witnessed what could truly be called a miracle of industry and devotion. Men worked day and night that the temple might be made ready within the time appointed, and the Lord has strengthened both mind and body of those engaged that the work might be accomplished. (Young Women's Journal, "Temple and Temple Work," Vol. 14, No. 2 (Feb. 1903), P. 51-56)

Again, no logistics about the actual work, just flowery language about miracles and devotion. This is the pattern we keep seeing in this story.

Winder comes up again in another Old World building narrative in Utah: the Hotel Utah, built between 1909-1911. Winder was 89 years old when given charge of the construction of that building, and wouldn't you know it, he died before it was finished. In the next post, I'm going to explain where the symbolism of the architect dying before a building is completed comes from.

Next we have the journal of Wilford Woodruff, but first a warning. This guy is a known liar, if you need reminded of that please re-read this post from Pure Mormonism. Woodruff recorded on April 11 of 1892 that he rode on the elevator and went through every room of the temple and commented that there was "a great deal of work yet to be done in order to get the work done by next April conference." This tells us that the elevator shafts were already built and elevators installed. Woodruff implied that the rooms were at least framed, but offers no other details. The entry is vague, and I think this is on purpose.

Remember, it was Wilford who challenged the Saints in the April 1892 capstone ceremony to pledge to come up with the money to finish the temple within a year. Was this money just for artwork, carpet, chairs and furnishings or did it also include rough lumber, trim, plaster, plumbing, electrical, and the rest of it? How are we ever to know without detailed work logs and clearer records of what really transpired inside the temple walls before and after 1892?

I believe the vagueness is a bait and switch; an effort to get us to focus on the spiritual/miraculous aspect of the story while ignoring the lack of logistical details. Quite genius if you really think about it.

Next we have contemporary newspaper articles.

This first one, published in the Deseret Evening News on New Year's day of 1893, reveals the following:

Between two and three hundred men are regularly employed at present, and no industrious hive presents a busier scene than that which is daily enacted within those massive walls. Those who do not know how much has been done during the past eight months, would not believe that all that is left undone can be completed in the remaining three. On the other hand, those who do know what has been done, have no particle of doubt that the eighty days left of the specified time will see everything finished and ready.

For obvious reasons, but little has been said or written concerning the work on the interior of the building, the part now receiving attention. From this it must not be inferred that there is little to impart of that the interest of the community has abated. The exact reverse is true. (Emphasis added)

Why would the article state that "but little has been said or written concerning the work on the interior of the building"? Isn't this a strange statement? What are the "obvious reasons" for this?

Was work on the interior really such a secret? Were they keeping it hush, hush: to keep the enemies of the Church from hindering the work?

Well that theory doesn't make sense, because in another article, it was claimed that the temple had been open to nonmember tourists and sightseers after the capstone and angel Moroni were placed.

The article, published in the Provo Daily Enquirer on April 14, 1892, states the following:

Because of vandalism at the Salt Lake Temple, the authorities have closed it against the general public...Strange to say, the Salt Lake Tribune views this arrangement with apparent favor, it says:

"Ever since the completion of the stone work of the temple and the setting of the statue in position, there has been a steady stream of sightseers going up those long flights of stairs to see the statue and get the superb view beheld from the upper platforms. But the privilege has been so shamefully abused that the church authorities have felt obliged to shut the gates against the general public, and hereafter admit only such as they have good reason to believe will not misuse the courtesy extended to them. The relic fiends have pulled strips of the heavy gilding from the lower part of the statue, besides scratching up the pedestal with knifes and pencils, and while, on the way up or down have even climbed scaffoldings in the interior to chip off pieces of plaster cornice to carry away as souvenirs.

Moreover, not being content with that, they have spit tobacco juice all over the premises, on the statue, on the stairs, and into the crevices of the wood and the stonework, where the nasty mess can only be reached with fine brushes. Then, several visitors have, within hearing of the attendants, expressed a fervent desire for dynamite that they "might blow up the whole damn thing, saints and all." In short, the visitors were making such ravages that something had to be done, and the only thing was to shut out the general public, as has been stated..." (See full article here)

The capstone ceremony took place on April 6, 1892, and this article was published only 8 days later. So for a full week the Church allowed the nonmember public to come into the temple and ascend the towers while 200-300 workmen were attempting to finish the interior?

Given the historical account of the LDS people's fear of outside persecution, it doesn't make sense that leaders would allow nonmembers inside the temple, especially right after a ceremony in which the "prophet" asked everyone to furnish money to finish the interior within a year. Why allow tourists in to slow down the workers? Why allow potential enemies into the building at all?

But if the temple was actually a pre-existing building in Utah, then it may have long been a tourist attraction in the area. Perhaps this had been going on for years before LDS leaders decided to repurpose the building into a "temple." Whatever really happened, strange articles like the one above seem anomalous and out of place in the "official" narrative.

No matter what we think history was, it is important to remember that we were not there. We did not witness it. All we have are documents written by people who are now dead, keep in mind that documents held by large institutions, with money to lose, have most likely been doctored, scrubbed, and varnished to portray a certain narrative.

Let me ask you, would you trust anything that the Vatican released as official history? I wouldn't. The same skepticism should be applied to the LDS Church, an institution now worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

I found two other articles reporting on the dedicatory services in 1893, read them here and here. They only offer descriptions of the interior work, and give us nothing about how the work was done, who did it, where the materials came from, or any other logistical detail.

The first article I quoted claimed that between 200 and 300 men were regularly employed on the interior of the temple. Who were these men? What were their names? What were their specific jobs? What were their wages? Where are any of their journals? Where are any journals of their wives and children?

Of those 200-300 men, I found just two journal entries where work on the interior is mentioned. The first comes from George Kirkham, a carpenter by trade. On April 22 of 1892, Kirkham reported being assigned to "dressing up some wainscoting for the basement of the temple." Later in June of 1892, Kirkham reports taking his family through all the rooms of the temple. Read the journal here.

The other man was William Asper. In a life sketch of him that is available, he only mentions work on the Salt Lake Temple once. He wrote, "In early 1893, I got a request for six more staircases for the Salt Lake Temple." And that's his only entry for 1893. What specific staircases? He does not say. Read the entry here.

These journals give us next to nothing for construction details about the interior. Kirkham's journal implies that the rooms were at least framed by June of 1892, but offers little else. It should be noted here that the only photograph of interior work was taken of the Assembly Room sometime in 1892. Here it is again so you don't have to scroll back up:

This clearly shows the room being framed with rough lumber. This room is on the fourth floor of the temple, and we can clearly see a framed floor. But to get from this rough-framed state to a beautiful finish in under a year (without power tools) is a staggering accomplishment even for just this one room. Yet we're told that workers finished every room in the temple in the same timeline.

Again, I ask, what were these men's names? Where are their journals? Why can I find only two men who mention the interior work in their journals if there were 200-300 working full-time on the interior? This is not enough evidence to convince me that the LDS people actually built this temple and finished the interior.

Also keep in mind that not a single book has been written on the construction of the interior. In all the books I've read about the building of the Salt Lake Temple, the interior is only given a cursory mention...and that's simply because there are no documents available to research on it.

It's almost as if they want us to believe that the interior was built and finished by a collective abstraction. A faceless and nameless mass of workers who accomplished impossible feats with the "help of God." When we're dealing with a story that is overshadowed by elements of the miraculous, then timelines, logistics, and deadlines don't matter. These things can be whatever the narrators say they are. If God wanted the temple interior finished in only one year, then the nameless workers would accomplish the task.

There is one final thing to address before I end this post.

A Major Clue from Brigham Young

My next post will be the most important of this series. I will be tying all of the patterns and symbolism together in an effort to discover the intended meaning of the Salt Lake temple narrative. Remember, in the world of the occult, there are always two interpretations of information fed to the public: the exoteric and the esoteric.

The exoteric is the narrative fed to the masses, the story we are given about this world we inhabit. This includes the mainstream narrative about history, technology, medicine, health, banking, finance, war, government, etc., given to us through establishment education and the mainstream media. The esoteric, however, consists of hidden truths kept from us by the elites, who are members of powerful secret societies that conspire together to control our world and feed us a false sense of reality.

The key to telling the difference between the two is learning the language of the elites. They often give clues that are purposely hidden in plain sight so that their peers understand the messages while the masses miss them. I have found one of these clues in the Salt Lake temple narrative that I will share here to segue my transition into the next post.

This is found in the Journal of Discourses, and was uttered by Brigham Young on April 22 of 1877:

In the days of Solomon, in the Temple that he built in the land of Jerusalem, there was confusion and bickering and strife, even to murder, and the very man that they looked to give them the keys of life and salvation, they killed because he refused to administer the ordinances to them when they requested it; and whether they got any of them or not, this history does not say anything about. (JD 19:-220-21)

There is so much to unpack here in this one paragraph, but I'll be brief because when you read my next post you'll understand it perfectly.

First of all, there were no Old Testament prophets killed during the time when Solomon's temple was being built. The three contemporary Israelite prophets during this time were Nathan, Iddo, and Ahijah, none of which were murdered by men seeking ordinances. In fact, none of these prophets revealed or administered any sacred ordinances to Solomon or his people. If they did, it has been omitted from the Biblical account.

So who is Brigham Young talking about?

He's referencing Hiram Abiff. Remember it was Abiff who the Masons believed was murdered in Solomon's temple before it was finished. He was killed by the three ruffians, fellow-crafts who were seeking to extort Abiff to reveal to them the lost word, which Brigham veils by calling it "the keys of life and salvation." The ruffians asked Hiram three times to give them the lost word and he refused each time, which ultimately got him killed. Brigham finishes his paragraph with referencing the lost word, by declaring that the "history does not say anything about it." This was his way of saying that the lost word has still not been discovered.

He made this statement in a public meeting, and he would have known full well what other Masonic brothers were in attendance in that meeting and to what degree they had been initiated. Brigham knew that some of the men there would know that he was talking about Hiram Abiff and others (who perhaps were not Bible readers) would assume he was talking about some Biblical prophet. This is a perfect example of a public figure hiding esoteric knowledge in plain sight while addressing the masses.

Why is this important for the temple construction narrative? Because in the paragraph before this Brigham is declaring that the St. George temple would be the first temple built to the "Most High" in which the ordinances for both the living and the dead could be performed, "since the one built by Solomon in the land of Jerusalem." He is speaking as if the Kirtland or Nauvoo temples never existed or were never used to perform ordinances. He is essentially saying that only the temples in Utah (St. George being the first) were offering the true ordinances from Heaven.

But this is also veiled language. What he is really saying, in my opinion, is that these temples (found in Utah) could finally be used to perform LDS slanted Masonic rites (his own mixture of "Celestial Marriage", i.e., polygamy, with Freemasonry) that he believed had been lost since the days of Solomon. And even more importantly, this veiled reference to Hiram Abiff is a major clue that the historical construction narratives of these buildings, specifically the Salt Lake temple, are not literal histories at all, but are rather ancient rituals subtly embedded into the official story.

Join me on the next one for a deep dive into this symbolism as it applies to the Salt Lake temple...

.jpg)

.jpg)